lesson 1:

Can the world stop genocide?

As the UN convention against genocide turns 70, its failures are tragically apparent

Squatting on a un refugee agency mat, clutching her listless two-year-old, Setera Bibi tells her story. Last year, at 4am on August 25th, the 23-year-old was awoken by gunfire. Fifty soldiers were rampaging through her village in north-east Rakhine state, in the west of Myanmar. Entering her house, they grabbed her husband. Four hours later he was returned, his beaten and bloated body wrapped in his own longyi. He had been tortured to death.

Latest stories

The survivors eke out their days in a small hut in the world’s largest refugee camp, Kutupalong, just inside Bangladesh. Ms Bibi’s mother cannot even walk now. She hopes her remaining daughter, Adija, will not recall much of the horrors. But her desolate eyes tell their own story. Malnourished, with a chronic cough, she is too weak to go to school. All three subsist on a ration of just rice, pulses and cooking oil. Asked about the future, she dare not think beyond the end of the week.

There are now 900,000 Rohingyas in the 27 camps on a spit of land called Cox’s Bazar. Most have similar stories to tell—of loved ones beheaded in front of their eyes and of babies thrown onto the flames. About 80% arrived in the last four months of 2017, fleeing an onslaught that killed at least 10,000 people—probably far more. Men were particular targets; 16% of those in the camps are single mothers.

The Rohingyas’ suffering clearly meets the criteria for “genocide”, as set out in the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide passed by theun on December 9th 1948—ie, acts intended “to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group”. A report for the un Human Rights Council recommends that the commanders responsible face trial for genocide.

Seventy years after the passage of the un convention, the world still fails to prevent such crimes, let alone punish those responsible. So it is with humility, anguish and some shame that human-rights advocates, politicians and un officials have been marking the anniversary.

Besides the Rohingyas, they will have in mind the Yazidis, an ethno-religious group mostly from northern Iraq. In 2014 Islamic State jihadists tried to erase their faith. They shot Yazidi men, kidnapped children and forced women and girls to become sex slaves. Roughly 10,000 were murdered, out of a global Yazidi population of perhaps 500,000. Some 300,000 fled to squalid refugee camps in Iraqi Kurdistan. The slaughter of men and mass rape of women has devastated Yazidi extended families. And the survivors now hate their Muslim neighbours, making it hard for them to co-exist in the future. Jan Kizilhan, a trauma specialist, says he fears that Yazidi society has been irreparably broken.

The genocide convention, drafted by Raphael Lemkin, a Polish Jew, was passed unanimously by the newly minted un. The next day the un also passed the “Universal Declaration of Human Rights”. The two documents were conceived largely in reaction to Nazi atrocities.

At the Nuremberg trials in 1946, 24 Nazi leaders had faced charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity—mass-enslavement, murder, conspiracy, persecution and more. Lemkin, however, was concerned with the Holocaust, the murder of 6m Jews by the Nazis. He even found a word for what Winston Churchill had called “a crime without a name”—genocide.

It took time for his new concept to be accepted. Stalin signed the convention but carried on slaughtering people regardless. America, worried that the convention would expose it to scrutiny for the decimation of native-American tribes in the 19th century, ratified it only in 1988. Britain, fearful of the implications for its colonies, ratified it only in 1970. Overall, 149 states have now acceded to the treaty.

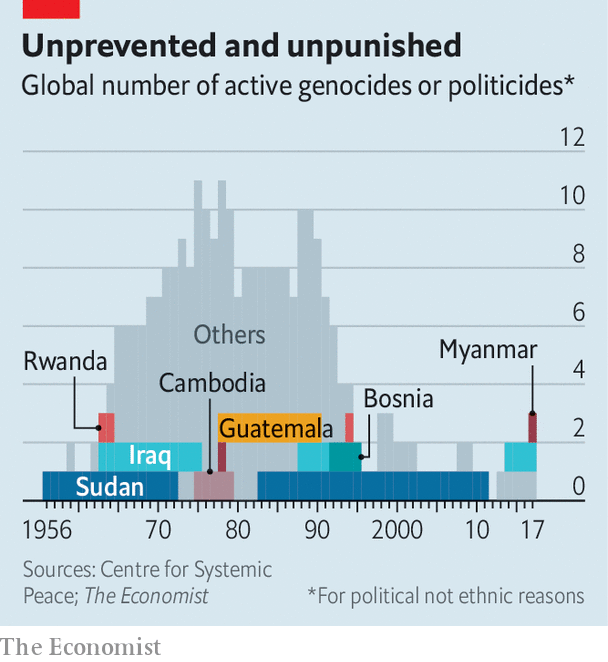

It has not come close to stopping genocide (see chart). A Tutsi government in Burundi massacred hundreds of thousands of Hutus in 1972. Pol Pot’s communist Khmers Rouges murdered 1.5m Cambodians, a quarter of the population, in 1975-79. In Guatemala, the army killed about 60,000 Maya peasants during a civil war in the early 1980s. Saddam Hussein’s regime killed about 100,000 Kurds in Iraq in 1988.

This catastrophe, followed by the butchery of Bosnian Muslims at Srebrenica in 1995, at last galvanised action. An international war-crimes tribunal had been set up in 1993 by the un to try those responsible for atrocities in the former Yugoslavia. Another court followed for Rwanda, and in September 1998 Jean-Paul Akayesu, a Hutu politician, became the first person ever convicted of genocide. In May 1999 Serbia’s president, Slobodan Milosevic, was the first serving head of state to be accused of crimes against humanity; genocide was later added to the charges. He died in custody before sentencing. In 2006 a court was set up in Phnom Penh to try former Khmer Rouge leaders. Last month it at last convicted two—Nuon Chea, aged 92, and Khieu Samphan, 87—of genocide.

In 2002 the International Criminal Court (icc) was founded. In 2010 it indicted for genocide a serving head of state, Sudan’s president, Omar al-Bashir. He is accused of ordering the destruction of three ethnic groups in Darfur. Meanwhile, in 2005, a un resolution on the “Responsibility to Protect” had given the un Security Council a broad new duty to intervene to prevent atrocities.

A plethora of private and public initiatives now seek to give advance warning of potential genocides, and to hector governments into action. The Australian National University, for example, publishes lists of countries at risk of genocide, as does the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Simon Adams, head of the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect, founded in 2008 to promote the doctrine, says there have been some successes. Kenya verged on all-out inter-ethnic violence after a disputed election in December 2007. But swift diplomatic intervention cajoled the two sides into talking. Ivory Coast came back from the brink in 2011 after French and un troops overthrew a blood-spattered president, Laurent Gbagbo.

Since then the outlook has darkened. Fighting in the Central African Republic was seen as the “early signs of genocide” by the un in 2017. The term has also been applied to the bloodbath in South Sudan, the depredations of Bashar Assad in Syria and Islamist attacks on Christians in Nigeria’s middle belt. Some groups do not even bother to hide what they are doing. Islamic State in Syria and Iraq published explicit rules about the duty of the pious to exterminate infidel men and rape infidel women. Meanwhile, Mr Bashir flaunts his continued liberty, breezily hopping from country to country that should be arresting him, eroding the icc’s authority.

What has gone wrong? Clearly geopolitics plays a role. Permanent members of the un Security Council have always shielded their allies. In Sudan, during the period of the worst killing in Darfur in 2003-04, America and Britain turned a blind eye to the actions of the janjaweed militias in exchange for intelligence from Khartoum about al-Qaeda. Russia will deflect any attempts to take action against the Syrian government. China, with economic interests in Myanmar and an aversion to any meddling in countries’ internal affairs, will protect it from referral to the icc.

Yet there are also structural reasons why genocide has proved so hard to prevent. The world has unwittingly created a hierarchy of suffering. Philippe Sands, a human-rights lawyer, argues that the creation of the crime of genocide has meant that “when the perceived lesser horrors occur, there is no reaction, and when it gets to genocide it is too late.”

To prove genocide, prosecutors have to demonstrate intent. This can take years of painstaking work. As Mukesh Kapila, a humanitarian official who witnessed the genocides in Rwanda and Darfur, puts it: “By the time you have established that all the criteria have been met, it’s over.”

Take the Rohingyas. They had been persecuted and murdered for decades, yet nobody acted. The determination of genocide eventually came over a year after the mass exodus. So much for “prevention”. Indeed, because the 1948 convention obliges countries to act on a genocide, it often discourages them from such a designation. During the Rwandan genocide, an American official memorably warned against calling for international investigations, because a genocide finding would commit his government “to actually ‘do something’”.

Theun report on the Rohingyas showed the hierarchy at work. It argued that the Myanmar army was also guilty of crimes against humanity among other ethnic minorities, the Kachin and Shan. Yet with attention focused on the charge of genocide in Rakhine, these crimes barely merited a mention in public reactions.

Lemkin and later scholars conceived of genocide as a process, moving from stigmatisation and dehumanisation through violence and terror to eventual annihilation (“in whole or in part”). Certainly, genocides are usually preceeded by stigmatisation and dehumanisation of the intended victims. But few laypeople would regard stigmatisation as genocide. The word literally means killing a people.

Perhaps it is time, suggests Mr Sands, to end the hierarchy of suffering by creating one catch-all crime of mass atrocity, fusing genocide and “crimes against humanity”. This would give states more scope to act before events escalate to a Rwanda or Myanmar or Syria. Drones, satellites and mass-data collection ought to make it easier to detect the warning signs.

Nhận xét

Đăng nhận xét